The Federal Reserve is waging a jihad against the savers and retirees in the United States, and the central bank must end this practice, stresses David Stockman, former Reagan budget director and bestselling author of “The Great Deformation.”

Speaking in an interview with the Fox Business Network on Wednesday, Stockman explained “that the jig is up” and 80 months of near zero interest rates “is crazy enough” and it’s harming savers and retirees.

According to Stockman, it’s now time for the market to dictate interest rates and what the right number is. Essentially, the interest rate shouldn’t be determined by 12 people sitting on the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC).

“There are savers out there millions. There are borrowers out there — millions. Let them figure out the right rate, not 12 people sitting on the FOMC,” he said.

Stockman added that the two percent inflation target rate established by the Fed is “totally made up” and is meant to “shovel free money into Wall Street.”

“It never does get to Main Street,” Stockman stated. “The whole idea of zero interest rates is to get consumers and households all jiggy and get them borrowing and spending, but that doesn’t work anymore because we’re at peak debt. Households have $13 trillion of debt. Ninety percent of households are tapped out. They can’t borrow, regardless of the interest rate.”

The Fed can’t stimulate the economy by choosing between savers and borrowers. Ultimately, says Stockman, the Fed should be a neutral body that refrains from intervening into the financial markets.

Fed vs. Markets: Who Should Say What Rates Should be

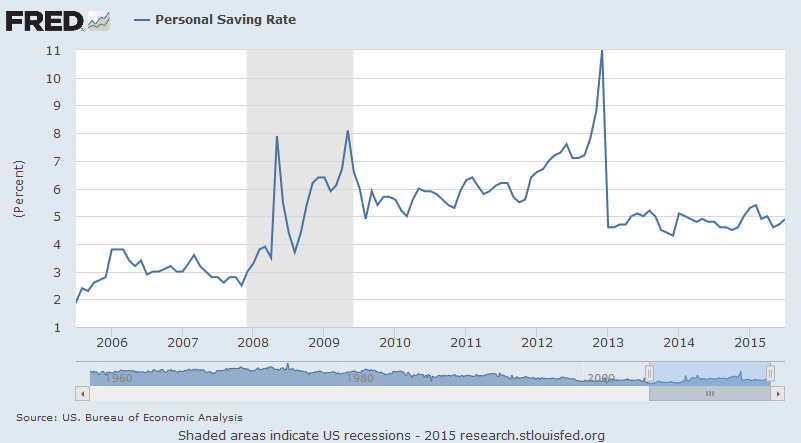

In the U.S. today, the national savings rate is just under five percent. The savings rate has been in single digits for much the past couple of decades. It has only reached double digits a couple of times in this time frame, including once at the end of 2012.

But one can’t blame people for not saving enough. What incentive is there? If you place $1,000 into a savings account you will only get a return of a nickel each month (if that). This is due to destructive Fed policy.

It’s imperative and necessary that the market tells us what the interest rate is.

Interest rates act like prices in the sense that it gives us signals if consumers are saving or spending, if businesses are expanding or holding steady, if banks want to loan out funds or build capital. When rates are low, savers have accumulated enough resources, which means businesses will then borrow to finance new projects that may not have been feasible before. When rates are high, savers haven’t accumulated enough resources, which means will have to maintain the status quo.

Just because the Fed lowers rates artificially it doesn’t mean resources will suddenly come out of nowhere; savers may not have set aside enough funds and companies may not have enough money to invest in long-term projects.

In most cases, the Fed and governments refrain from intervening in prices (we see the ramifications of this act before). So why do they dictate interest rates?

Artificially low rates come with a plethora of unintended consequences. One of them is that borrowers accumulate too much debt because they are incentivized into putting themselves into debt by central banks and governments. Another unintended consequence is the distortion of the marketplace.

Tom Woods does an excellent job explaining this part of the equation:

“If the low interest rates are brought about artificially, as when the Fed pushes them down, a problem arises. Additional resources do not magically appear just because the Fed has forced down interest rates. The public has not saved the necessary resources to make possible the completion of all the new projects. With a vast increase in the number of market actors using freshly borrowed money to buy an unchanged supply of factors of production, the prices of the factors rise. It soon becomes clear that the factors of production do not exist in sufficient abundance to make all of these projects profitable. The bust sets in.”

He adds:

“The Fed’s manipulation of interest rates, in short, disrupts their coordinating function. It distorts the path of investment and causes investors to make decisions they wouldn’t have made if the Fed’s interventions into the market hadn’t prevented them from seeing the economy’s true state of resource availability.”

It’s this type of government and central bank intervention that leads to all of the malinvestment, the misallocation of resources, the booms and the busts. Yet, for whatever reason, the free market takes the blame. Twelve people sitting in a room isolated from the rest of the economy can’t pick a random number for interest rates. Only a market made up of millions of savers and spenders, borrowers and businesses can.

Leave a Comment