By: Ali Mecklai

Recent data published by Yardeni Research Inc., Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the Institute of International Finance (IIF), and in the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Economic Data (FRED) database offers an insight into the true extent of central banking practices before and during the covid-19 pandemic.

The wide-ranging implications of this can be seen through several critical dimensions. But first we must understand the destructive nature of central banking.

If we accept the main premise of central banking, that the central bank is the lender of last resort, it follows that in this last resort event the central bank must have a pool of wealth to lend from. After all, in order to lend to someone, you have to own something of value. In this situation, the central bank prints money, which, to that extent, is where it derives its pool of assets for lending from, taking from people via inflation. Paradoxically, the central bank therefore lends to banks by stealing from the people, whereas the banks are then expected to loan that money back to people. This theft is, however, subtle, not seen as a direct tax or immediate confiscation, but through the destruction of real savings and purchasing power.

From the beginning of this year to June, the total assets of major central banks (the Fed, ECB, BOJ, PBOC) have jumped by a near $6 trillion. This rapid ascent is likely going to continue as the year progresses. Similarly, in Q1 of this year, global debt rose to $258 trillion, representing an all-time high of 392 percent of GDP. Households, businesses, and governments are taking on more debt in hopes of offsetting the acute economic pains of the crisis. But the false sedative of debt will soon dissipate, revealing the true pain behind all these distractions. Make no mistake, what is being done by governments and enabled by central banks is akin to paying credit card debt with more credit cards.

This data should alarm you and the immediate question should be, Who’s going to pay for it, and who benefits? In the bizarre world of negative interest rates, however, that question becomes all the more complicated.

Artificially low interest rates have enabled the longest bull run in US history (2009–20). Cheap borrowing has propped up unprofitable zombie corporations which rely on loans to pay back loans. In conjunction with quantitative easing efforts, the S&P 500 has not only recovered since the covid March meltdown but surpassed its all-time high.

Low interest rates have historically made it cheaper to mortgage a house, finance a car, and pay for student debt—in the long term, however, it has made all of these more expensive. By enabling cheap borrowing to finance spending, particularly on assets such as housing and in the equities market, central banks have infused those markets with artificial demand which in turn causes prices to skyrocket.

By indirectly monetizing and devaluing the real value of debt, central banks have cut the brake wires off government spending.

Source: Edward Yardeni and Mali Quintana, Central Banks: Monthly Balance Sheets (Yardeni Research Inc., Aug. 27, 2020), figure 6.

Its no coincidence that the moment the Fed started to unwind its balance sheet in 2018 markets went berserk. When the Fed shrank its assets by just around 6 percent between early 2018 and February 2019, the market plummeted by twice that.

The most recent market faltering in March was a very real indicator of upcoming economic trouble. It was all covered up by the Fed, however, which bought $500 billion in Treasury securities and $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities to provide so called “emergency liquidity.”

In effect, the Fed’s actions diverted scarce resources from productive sectors to monetize government debt, inflate a chaotic asset bubble, and send the bill to everyone else. Importantly, this has created an environment of haves and have-nots. So, although so-called conservative politicians are scratching their heads about the popular rise of socialism, should we really be that surprised?

The true mark of economic recovery should not be measured nominally in dollars and cents, but in terms real interest rates. When markets, not bureaucrats and central bankers, set interest rates, markets equilibrate, allowing for productive and allocative efficiency. The true sign of a growing and healthy economy should instead be a positive real interest rate set by market forces.

Positive real interest rates indicate that investments/savings are yielding positive returns and thus creating wealth. This means that people, businesses, and governments are rewarded for saving. In the world of negative interest rates, the opposite is true.

When real interest rates are negative, they create distortions in markets. Consider that between March 23 and the day I write this (August 8), nearly every popular US asset has inflated. Equities such as the NASDAQ and S&P 500 have risen by 61 percent and 50 percent respectively, bitcoin by 81 percent, and gold by 36 percent. Through the manipulation and debasement of currency, however, this asset inflation should be a warning signal to everyone not that their assets are necessarily worth more, but their dollars worth less.

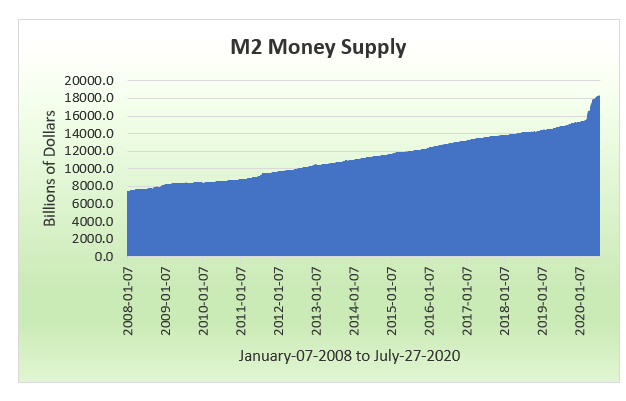

This asset inflation coincided with a sharp M2 money supply increase (roughly 20 percent year over year).

Nonetheless, when real interest rates are negative, bubbles are to be expected. Since the covid crisis, ten-year inflation-indexed bond yields have crashed, falling even below –1 percent.

Source: FRED (10-Year Treasury Inflation-Indexed Security, Constant Maturity [DFII10], accessed Aug. 26, 2020), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DFII10.

Unsurprisingly, these rates have dropped so low not particularly because their yield is negative (although they did dip below that level slightly in March), but because inflation is higher than the yields.

This is something that the traditional CPI (Consumer Price Index) will fail to capture. Using irrelevant baskets of consumer goods such as air travel, nightclubs, and hotels among other things paints a false picture. Of course, now more than ever there is more money chasing fewer goods, with many businesses being closed and stimulus checks coming in. The recent sharp increase in the money supply will therefore drive real inflation even higher and real interest rates lower.

Source: Fred (M2 Money Stock [M2], accessed Aug. 17, 2020), https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/M2.

Real negative rates serve to accelerate global indebtedness and solidify zombification. As the balance sheets of central banks grow, so does the indirect subsidization of inefficient corporations. By taking out corporate loans at a real interest rate of below zero, zombie corporations manage to have their lender of circumstance actually pay them for taking on debt. By keeping inefficient players in the marketplace, innovative entrepreneurs are blocked from creating wealth and market barriers to entry are raised through a slow and steady engulfment of scarce resources, furthering an unprecedented inequality of wealth via central bank–induced monopolization.

In 2019 the BIS determined that over 10 percent of the publicly traded firms of fourteen developed countries were zombies. My assessment is that by the end of this crisis that statistic will be much higher. In the US, the number is nearly 20 percent according to Deutsche Bank Securities.

When borrowing money is so cheap (in fact, they pay you!) zombification is an inevitable process. Analyzing quarterly data from 1998 to 2020, 8 percent of the variance of corporate debt levels as a percentage of equity can be directly attributed to changes in M2 levels. Utilizing regression analysis, the null hypothesis of this relationship (that the variables are unrelated) has a p-value of 0.0000 and a t-score of 588, or in other words there is an almost 100 percent chance that the relationship between these two variables is statistically significant.1

Japan is the historical home of zombies and is still suffering from the peak of its crisis in the eighties. As of 2018, Japanese corporations had taken out $4.59 trillion in loans, the highest amount since 1997. Japan’s myriad economic problems not only include the zombification of its companies but also of its people, as they face the challenges of an aging population. As its balance sheet surpasses 100 percent of GDP, the BOJ is essentially doubling down on past failed policies.

Source: Edward Yardeni and Mali Quintana, Central Banks: Monthly Balance Sheets (Yardeni Research Inc., Aug. 27, 2020), figure 5.

Keeping inefficient zombie corporations may boost short-term employment by avoiding the general turnover of firm market share; however, in the long term they massively drain resources and block future employers out of the marketplace. The BIS writes:

Specifically, the estimation results suggest that a 1 percentage point increase in the narrow zombie share in a sector lowers the capital expenditure (capex) rate of non-zombie firms by around 1 percentage point, a 17% reduction relative to the mean investment rate. Similarly, employment growth is 0.26 percentage points lower, an 8% reduction. However, under both definitions we find that non-zombie companies invest more and have higher employment growth.

Following the 2008 crisis a radical experiment of depressed and even negative interest rates was employed by the Fed, BOC (Bank of Canada), ECB (European Central Bank), and other central banks. Now, however, the resources that were previously available to fight recessions have been totally depleted combating the last recession. Fighting debt with debt is irresponsible and unfair to future generations—clearly fiscal and monetary restraint is needed.

The interplay between rising debt levels, negative real interest rates, and zombification should concern us all—especially in the context of global lockdowns. But it should not be capitalism which we blame for this crisis. Quite the contrary, in fact; we should blame central banking and its destructive economic capabilities.

This was originally published on Mises.org.

Leave a Comment