By: Sammy Cartagena

With June 2021 CPI growth being at a thirteen-year high, inflation has been on a lot of people’s minds lately. You can’t blame them, seeing as over 23 percent of all dollars in existence were created in 2020 alone. Although future inflation is certainly an important concern, in this article I instead focus on the chronic inflation this country has faced for over a century.

Under normal circumstances, when most people think about inflation, they likely think of a gradual rise in prices averaging out to 2 percent per year. Most people think nothing of this inflation and simply consider it a part of life, or a necessary part of a growing economy. I am here to argue that not only is this 2 percent inflation number a lie, but also that a more harmful aspect of inflation is often ignored: the price deflation that never comes to be.

For the past few decades, the Fed has historically sought to achieve a 2 percent yearly inflation target. They measure this target through the Consumer Price Index (CPI), a weighted basket of consumer goods used to estimate overall price levels for the “average” consumer. There are several problems with using CPI as a metric.

First, the items composing CPI are by nature subjective and arbitrary, as there is no objective way to measure a single value of money, since money is necessarily expressed in terms of other goods. Additionally, the components of CPI comprise consumer goods people can afford, so if a good becomes too expensive for consumers to purchase, it will no longer be included in the CPI. This is called substitution bias. When the price of a good rises, people will find substitutes, meaning it is likely this good will be phased out of the CPI basket. This means the goods that are increasing in price at a substantial rate (and would indicate a higher inflation rate) are taken out of the weighting. Additionally, monetary expansion often leads to shrinkflation in goods, whereby the quantity or quality of a good is reduced in lieu of a price increase, rather than outright price increases. It is much harder for CPI to incorporate discrete changes in quality or quantity of a good compared with simply an increase in price.

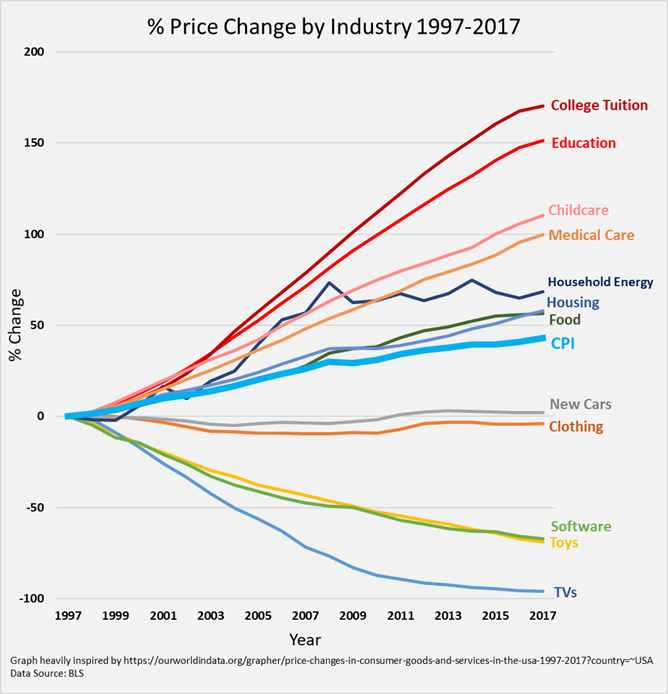

Even if you were to ignore these issues and take CPI numbers at face value, it is still illuminating to look at the differences in price change in the different industries comprising CPI.

The following are a graph and table measuring percent price change by industry from 1997 to 2017. Overall CPI increased by approximately 43 percent over this period, but industries such as education, childcare, and medical care increased by far more, and industries such as software and TV decreased in nominal price over this period.

|

Industry Price Changes, 1997–2017 |

||

| Industry | Total % Change | Avg. % Yearly Change |

| College Tuition | 170.1% | 8.5% |

| Education | 151.1% | 7.6% |

| Childcare | 110.2% | 5.5% |

| Medical Care | 99.7% | 5.0% |

| Household Energy | 68.4% | 3.4% |

| Housing | 58.0% | 2.9% |

| Food | 56.5% | 2.8% |

| New Cars | 2.1% | 0.1% |

| Clothing | –3.9% | –0.2% |

| Software | –67.2% | –3.4% |

| Toys | –68.9% | –3.4% |

| TVs | –96.0% | –4.8% |

| CPI | 42.9% | 2.1% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Although yearly CPI growth averaged 2.1 percent over this twenty-year period, college tuition increased at over four times this rate, at 8.5 percent per year. Prices in industries such as childcare and medical care also increased far faster than overall CPI.

What is interesting to note about the industries that saw decreased prices is that they are sectors where either increases in technology have caused huge growth in productivity or where the US has outsourced production to other countries such as China. Not only is inflation decreasing our overall purchasing power in a chronic fashion, but this overall CPI increase exists even despite the issue of substitution bias and the massive price deflation in certain industries. If CPI did not include these massively deflationary industries, we would better see the true harm from inflation.

The industries with large price increases are precisely the industries that have seen less growth in productivity, so they give better insight into the effects of monetary inflation. Education, childcare, and medical care are all well established, labor-intensive industries, meaning that an increase in capital and technology generally has less of a deflationary effect on the prices of their products. Compare these industries to the relatively new TV industry, where improvements in production are occurring at a rapid pace.

The question then arises: If CPI does not do an adequate job of measuring inflation, how should we measure it?

The original meaning of inflation, and the one that Ludwig von Mises used, was defined as an increase in the supply of money. This leads to a decrease in the purchasing power of money (PPM), but this decrease in PPM is a result of inflation, not inflation itself.

In Austrian theory we know that the purchasing power of money is determined by 1) the total demand for money to be held as cash balances and 2) the stock of money in existence. Based on this knowledge, measuring the change in the money supply can give us important insight into one of the two factors that determine PPM. In this case, M2 is used, which includes cash, checking deposits, and highly liquid money substitutes such as saving deposits and money market securities.

Using BLS data we find that the M2 money supply grew from $3.83 trillion in 1997 to $13.22 trillion in 2017, for an average yearly increase of 12.25 percent.

This 12.25 percent is far higher than the 2 percent inflation we are repeatedly told to believe is occurring. The large disparity between M2 growth and CPI inflation can be partially accounted for based on the increased productivity that comes about from an increase in capital per person and the existence of new technologies. These factors contribute to an increase in quality of life for all people in a progressing economy in the form of lower prices, but current monetary expansion not only stifles these positive deflationary forces, but also brings about nominal price inflation.

Additionally, since money is not neutral, new money entering the economy will not raise prices or wages uniformly. The recipients of new money creation benefit, while everyone else tends to lag behind. Empirical data support this conclusion, seeing as real wage rates of nonmanagement private sector workers have been practically stagnant since the 70s, even with large increases in productivity. Regardless, the Cantillon effect tells us that the first to receive and spend newly created money benefit at the expense of the rest of society, since they get to buy goods at their original prices and by the time this new money is received by others, the prices of goods have already increased.

Conclusion

In addition to causing distortion in the economic structure and setting off the boom-bust cycle, monetary expansion causes a tangible negative effect in the lives of all consumers. It harms saving, eliminates the increase in the purchasing power of money that would come from economic growth, and siphons resources away from the private sector.

The deflationary effects of increased productivity can obscure the negative effects of monetary expansion, but inflation becomes much more visible when looking at relatively more scarce goods such as real estate, education, and equities. These are all things that are pivotal in our lives but severely underrepresented in CPI and becoming progressively harder for middle-class workers to obtain.

We should avoid the misconception that inflation has largely been “mild” for the past several decades and realize the full consequences that central bank policy has in our everyday lives.

This was originally published on Mises.org.

Leave a Comment